- Home

- Fungi

All images on this website have been taken in Leicestershire and Rutland by NatureSpot members. We welcome new contributions - just register and use the Submit Records form to post your photos. Click on any image below to visit the species page. The RED / AMBER / GREEN dots indicate how easy it is to identify the species - see our Identification Difficulty page for more information. A coloured rating followed by an exclamation mark denotes that different ID difficulties apply to either males and females or to the larvae - see the species page for more detail.

Fungi

Fungi are not plants, as was thought to be so in the past, but in a separate Kingdom of their own. In most cases, the main body of the fungus is hidden from view. It is a network of threads (hyphae) collectively called a 'mycelium', which permeate the substrate on which the fungus grows. The hyphae absorb nutrients and water from the substrate. The reproductive spore-producing structures, such as the familiar mushroom or bracket, are the visible parts of the fungus.

The Fungus Kingdom is extremely diverse, and includes many microfungi that are rarely recorded. Most of the larger species are in one of two major divisions or Phylum, based on the way the fungus reproduces. Basidiomycota (sometimes called 'spore-droppers') include mushrooms and toadstools, brackets, corals, puffballs, jellies, rusts and smuts. The Ascomycota or 'spore-shooters' includes cups, morels, yeasts and many other smaller fungi.

Taxonomy is very complicated and is liable to change as the true relationships between species are worked out. In the sections below, we have grouped fungi into categories based on their structure and appearance rather than their place in the scientific taxonomic hierarchy. There is more information under each section.

Recording fungi

Always note the substrate or host-plant on which the fungus is growing, and the habitat. To identify many large species, it is helpful to get a good photograph of the cap (from the top), the gills or spore-producing structures (from underneath) and the stipe or stem (from the side) - three images from three angles, rather than images from much the same angle.

Always note the texture of cap and stipe; the smell; and the presence of any staining or 'milk' produced when the cap, gills, stipe or body of the fungus is bruised.

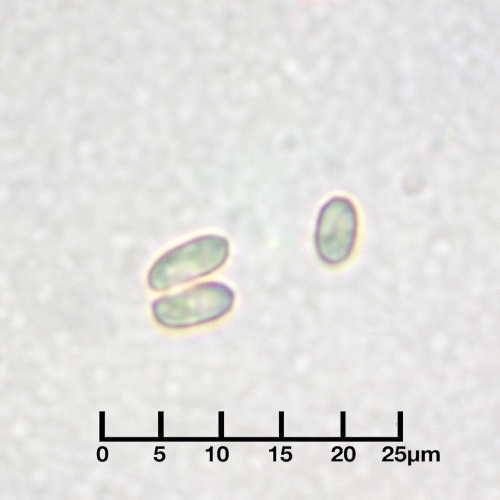

The colour of the spores can be very helpful. It is best seen by taking a spore-print from a collected specimen - advice on doing this is in many of the resources below. For some fungi, microscopic examination of the spores may be needed for identification.

Resources

The Leicestershire Fungi Study Group is a great place to start if you want to learn about fungi. They welcome new members. Their annual programme of study forays is led by enthusiastic and knowledgeable leaders. There are also indoor microscopy sessions held in Leicester. This is a really excellent way to broaden your knowledge, and make friends who share your interest in fungi.

There are many field guides, but none of them contain all the fungi you will find, or have all the photos or information you need, so it is a good idea to check several different books and websites.

- Courtecuisse, R. & Duhem, B. (1995) Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain & Europe. Collins

- Kibby, G. 2020-2022. Mushrooms and Toadstools of Britain & Europe, Volumes 1 - 4. (privately published)

- Laessoe,T. & Petersen,J. (2019) Fungi of Temperate Europe. Princeton University Press, Volumes 1 and 2

- O'Reilly, P. (2016). Fascinated by Fungi. First Nature

- Phillips, R. (2006). Mushrooms (2nd edition). Macmillan.

- Sterry, P. & Hughes, B. (2009). Complete guide to British Mushrooms and Toadstools. Collins

- Wood, E & Dunkelman, J. (2017). Grassland Fungi: a Field Guide. Monmouthshire Meadows Group

Pat O'Reilly's First Nature website has some helpful advice and tips on identifying fungi.

The British Mycological Society website is a good source of information, mostly aimed at the expert.

If you know of other websites or books that you would recommend, do let us know: info@naturespot.org

Agarics and other fungi with caps and gills

In this section are most of the commonly recorded 'mushrooms and toadstools' with spore bearing gills underneath the cap. Most of these are Agarics and related species, but we have included some families that have caps and gills but are unrelated - e.g. the Russulaceae.

For most species, the spores fall from the gills and are dispersed by the wind. Spore colour is an important way of identifying species and it may be necessary to take a spore print from a collected specimen. As well as noting the colour, smell, texture, milk/staining, habitat and substrate, also note:

- the way the gills are attached to the stem or stipe; cutting vertically through the cap and stipe will help to see this (some examples are here: decurrent; adnate; adnexed/free)

- the colour of the gill edges (example: velvet shield)

- whether there is a ring around the stipe (some examples: wood mushroom; porcelain fungus)

- whether there is a volva or sac at the base of the stipe (example: false death-cap)

- whether there is a veil or the remains of one under the cap. (example: birch web-cap

Agaricaceae - Parasols, Mushrooms, etc.

Many species are difficult to identify without detailed examination of a specimen by an expert; often involving microscopic examination of the spores - and sometimes even experts cannot identify a species; in these cases, DNA sequencing is the only answer. The familiy includes many edible species, including the commercial mushroom Agaricus bisporus, but some are inedible or toxic. The species have a ring around the stipe. Spore print varies in colour; Agaricus are dark brown or purple-brown; Coprinus are black, the Parasols (Macrolepiota and Chlorophyllum), Earthcaps (Cystoderma) and Dapperlings (Lepiota, Echinoderma, Leucoagaricus and Leucocoprinus) are white or pale; the related Golden Bootleg (Phaeolepiota) has golden spores.

In the galleries below, an exclamation mark after the red or amber camera icon means that microscopic examination or information on smell, taste, texture or another factor is needed.

Amanitaceae - Amanitas

The Amanitas have both a universal veil and a partial veil. The universal veil is a membrane covering the entire developing fruit body, which ruptures as the mushroom grows to leave a sac at the base of stem, called the 'volva'. The remains of the universal veil can persist as fragments on the cap surface (e.g. the veil fragments of Fly Agaric are the white spots over the red cap). These can wash off in the rain. Some species have a large and very obvious volva and a bulbous base to the stipe; in other species it is less obvious and may be underground. The partial veil covers the gills underneath the developing caps, tearing as the cap expands to leave a ring of tissue around the stem of some species, which may persist or soon disappear. The Grisettes do not have a ring around the stipe. The stem can be more or less smooth, or covered in scales or woolly fragments, sometimes in a snakeskin pattern.

Cap colour and veil fragments on the cap can be very variable. The charactersitics of the stipe can be more useful as aids to identification. As well as photographing the cap, it is important to photograph the whole stipe from gills to base including the volva of a fresh mature specimen - not an old and damaged one. In one very variable species - The Blusher - a reddish stain appears when the flesh is cut or bruised.

This family includes soem of the most toxic British species. Note that the Rosegills (Volvariella and Volvopluteus) have a volva, but no ring.

Bolbitiaceae - Fieldcaps, Conecaps

Cortinariaceae - Webcaps

This is one of the largest and most difficult groups of fungi found in the UK; identification of most of the species requires microscopy and verification by an expert - occasonally, DNA sequencing is needed. Sometimes it is necessary to examine several specimens in a population at different stages of growth. All species have rusty-brown, warty spores. Cortinarius have a veil that leaves a woolly, thread-like or slimy covering on the lower stem and cap, sometimes very conspicuous, but in some species only a faint trace on the stem can be seen with a hand-lens. Note also that some species in other families may also have a veil.

Crepidotaceae - Oysterlings

The Oysterlings (Crepidotus) are small fungi commonly found on twigs, branches and stumps of broadleaved deciduous trees. They have the unusual growth habitat of being attached to their substrate by the cap, often to one side, with the gills fanning out from the point of attachment. This growth habit is also seen in the Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotaceae), but these are larger and have pale spores, unlike the darker buff or brownish spores of Crepidotus. Identification of Crepidotus to species is difficult, usually requiring microscopic examination.

In the gallery below, an exclamation mark after the Red camera icon indicates that microscopic examination is needed.

The genus was formerly placed in the Inocybaceae.